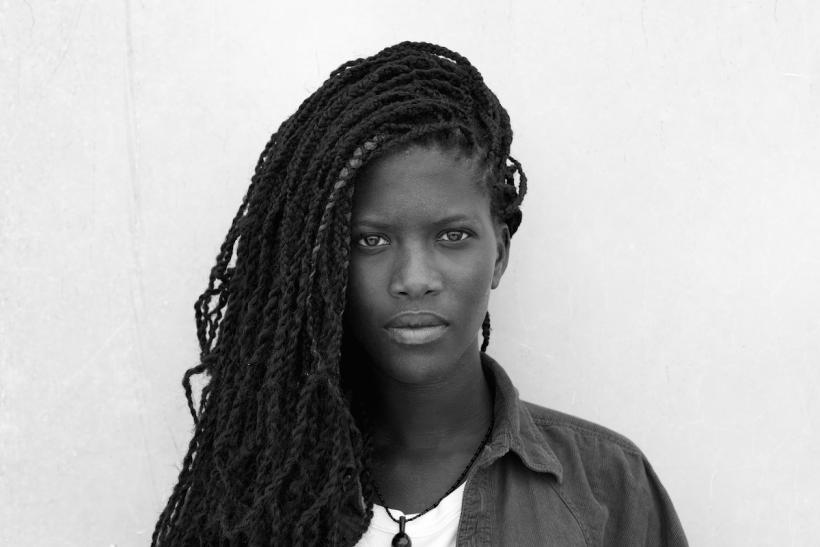

Over the years... I’ve realized that my father’s sentiments echo those of the judge, the father, and the rapist. Image: Thinkstock.

How do we, as a society, grapple with the concepts of guilt, making amends, and forgiveness when it comes to sexual violence?

Content notice: mention of childhood sexual abuse and sexual assaults against underage minors

I’m not going to say his name. I’m not going to give him the privilege of seeing his name in print again. He has enough privilege.

But if you’ve been paying attention to the news, you know to whom I am referring: the young white man, the swimmer, at the center of the Stanford rape case.

The young white man with the clean-cut do-over mugshot.

After being convicted on three felony counts of sexual assault, he has been sentenced to a mere six months in prison, of which he will probably only serve about three.

Prosecutors recommended six years, of the maximum 14, but Judge Aaron Persky reduced his sentence after noting his age and nonexistent criminal history. “A prison sentence would have a severe impact on him,” he said. “I think he will not be a danger to others.” Judge Persky is now embroiled in a controversy of his own following this ruling.

The father of the rapist believes his son has already been greatly negatively impacted, having paid a “steep price […] for 20 minutes of action,” as he put it.

Much has already been said about the way his privilege has insulated him from consequence, about the ever-pervasive victim blaming in public discourse, and about the inadequacy of the criminal justice system.

But in so many of these conversations, in our rage against the rape culture machine, we forget the survivors — the most important people in the fight against sexual violence.

For me, it’s hard to forget. I am a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, at the hands of family members. I have PTSD because of it.

But that’s not even what I’m most interested in talking about right now.

My father is a convicted child rapist. In the late '80s, when I was about 2 years old, he was convicted of multiple counts of sexual assault-related charges. He served about a decade in prison for his crimes. As a result, I grew up without him.

But in our small Queens, New York, neighborhood, his crimes haunted us. I still recall the shame I felt at the way some people looked at us, almost as if blaming us for what he did.

Of course, at that time, at that age, I didn’t fully understand it. The gravity of rape and sexual violence was such an abstract concept to me. I knew that my father had done “a bad thing” and that a child was involved, but that was the extent of my understanding at the time. (I would eventually learn that he raped multiple pre-teen girls.)

Once out of prison, he attempted to enter our lives again, though he was separated from my mother (they eventually divorced). He felt bad for the years he lost with us because of his “stupid mistake.” He wished so badly to be with us again, the way things were: a nuclear, intact Black family.

In a society where Black families are constantly pathologized, in neighborhoods and families where so many of my peers didn’t have their fathers (or didn’t have them the way they wanted), what tween girl wouldn’t want her father back?

I’m not sure we can truly answer questions about when perpetrators of sexual violence ought to be forgiven until abusers start admitting what they’ve done and adequately acknowledging the ways they’ve caused pain and trauma.

Over the years, though, I’ve realized that my father’s sentiments echo those of the judge, the father, and the rapist. He’s “served his time,” it “was a mistake,” Jesus “has forgiven him,” and he “deserves” for people to move past his crime.

And in a country with the highest incarceration rate in the Global North (particularly for the most marginalized populations), and in the light of success stories of reformed ex-cons, this mindset can seem alluring. It can even seem just.

But it feels, to me at least, that we come to these conclusions without actually asking questions, without going through the process of interrogating what the answers might mean, and — again — without considering the voices of those most impacted by sexual violence: survivors.

Ultimately, when it comes to the issue of individual forgiveness, there is no question (or at least there shouldn’t be) that that power lies in the hands of the individual victim vis-a-vis their rapist or abuser.

For some, total forgiveness is the only path, for religious, moral, or other reasons.

For others, there is no revenge or legal recourse hellish enough to soothe the wounds of trauma.

But how do we, as a society, grapple with the concepts of guilt, making amends, and forgiveness when it comes to sexual violence?

And what of their own guilt (if they have any)? Should they feel forever guilty? If so, what does that look like?

Personally, I would always feel guilty for doing something akin to what the Stanford rapist did — let alone like what my father did. And, speaking as a survivor, I think one should.

If most of us have to carry this trauma around for the rest of our lives in one way or another, the least you could do is continue to feel bad about that.

Ultimately, I’m not sure we can truly answer these questions until abusers start admitting what they’ve done and adequately acknowledging the ways they’ve caused pain and trauma. Our statistics on arrest, conviction, and sentencing with regard to sexual crimes leave a lot to be desired in that regard.

But it is only then that a society can make concrete decisions about how to deal with and collectively process our feelings about rape. It’s an issue we need to start thinking about now, if our hope is to eradicate — or at least significantly reduce — sexual violence. (And I hope that’s one of your goals, as a global citizen.)

The choices we make will have lasting effects not only on survivors and rape culture, but on our criminal justice system and efforts at rehabilitation as well.

The only way abusers will step forward is if we hold them accountable: Stop buying or otherwise supporting their work, stop associating with them, stop upholding them as community leaders, and call them out for their crimes.

Preventing the development of abusers requires an aggressive collective and individual effort to increase comprehensive sex education, foster healthy social development, and provide sexual violence education to children, youth, and young adults.

My father’s victims are probably in their late 30s to early 40s now. I sometimes think about them: I wonder how they’re doing, how they feel about my father and their trauma, what their lives are like (if they’re even still alive).

They probably wouldn’t want to hear from the child of their rapist, especially since I look so much like him.

But sometimes I wish I could apologize to them, hug them (if they’d be comfortable), and lament with them about the trust that was broken and the way they were failed by society.

And I wish essays like this didn’t have to be written and stories like this didn’t have to be told.